| 29. Technical Trends |

by Peter Mohilla and Robert Deaves |

|

The original design of the Finn featured a carvel construction in wood. The intention of Rickard Sarby was to create a boat which a skilful man could build completely by himself at home. Alternatively the sailor might have bought a wooden hull and fitted it himself according to his personal ideas. The technical development of the Finn is characterised by a steady change of three main factors: hull, mast and sail in regard with structural strength and flexibility.

The Finns in the fifties had wooden hulls in carvel, wooden masts and cotton sails. The hulls were generally leaky, the masts had a tendency to be too stiff or to break (frequently they did both), and the sails would shrink or stretch beyond measurement. |

|

|

|

Soon the German boat builder Mader pioneered with moulded plywood hulls. These boats did not leak and were fast in flat water because of their stiffness. By the same token this proved to be a disadvantage in heavy waves. In the UK, Fairey Marine produced hot-moulded hulls for home completion.

In the early sixties a fast combination for light wind was a stiff mast with a Fritz sail, unusable in medium winds and disastrous in strong winds. If you misjudged the weather forecast you'd be better off abandoning the racing in those days. In response Paul Elvstrom developed triangular masts and sails with flexible leaches but no Cunningham yet. You had to have a mechanism in order to control the halyard from the cockpit.

Before goosenecks were introduced, the boom was held in a slot through the mast and controlled by a wedge. Adjustment was only possible in theory on the beat. In the sixties these wedges were gradually replaced by a series of diagonal arrangements between the mast at deck height and the boom.

|

|

Sails and Masts

Cotton sails were used exclusively during the early years of the class until after the IFA authorised the use of dacron for sails in 1959, cotton sails soon faded away and dacron became the dominant cloth. In 1967, Sitka spruce from Canada was considered the best material for the mast, but was rare and very expensive in Europe. Many homemade masts were evident, some painted blue or white, but numerically superior were the stock masts from Elvstrom, Lanaverre, Newport, Collar etc. Many different types of sails were used: Elvstrom, Benrowitz, Raudaschl, North,

Jongkind. Although the Elvstrom sails dominated numerically, the Raudaschls were considered the best looking sails.

|

|

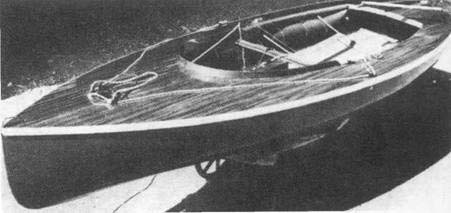

| Wooden Raudaschl hulls dominated Finn events in the late sixties |

|

|

In contrast Hubert Raudaschl built moulded wooden hulls. They were stiff locally but some had just the right flexibility overall in order to sag in the aft section on the reaches and runs, where they proved to be extremely fast. The best example was Willy Kuhweide's G 711. The disadvantage of these boats was that they collected a lot of water sailing in heavy air and it was difficult to sail them dry after capsizing. Attempts to build side tanks in these Raudaschl hulls proved to completely ruin their performance; the overall torsional flexibility, and thus their life, was lost. |

Also Raudaschl's attempts to build GRP and later sandwich hulls with the shape of his wooden boats proved to be unsuccessful. Only Lanaverre succeeded in this direction with GRP. The secret is to produce hulls, which are stiff locally, especially in the central and lower portion, but light in the ends and especially in the deck, and flexible against torsion overall. This can only be achieved with very high technology and experience. The percentage of glassfibre material must be as high, the percentage of resin as low as possible. Only very experienced builders are able to achieve this. Less experienced builders, let alone amateurs, tended to produce heavy boats which were too flexible locally but too stiff overall against torsion.

Early Seventies

In the early seventies the most successful combination was a flexible wooden hull from Raudaschl, a mast made by Bruder of Brazil and a sail from Raudaschl. The Bruder masts had a very flexible top sideways which opened the leach of the sail in the gusts. By that time the halyards had a lock at the mast top and the sail a Cunningham. This allowed the sailor to adjust his sail for a wide variety of wind forces. The best masts were the most flexible ones. Inevitably once you got into a very heavy gust or capsized they broke and you had to phone for a new one.

After Elvstrom retired from active Finn sailing, his sails and then his hulls carried on winning internationally. He had developed his own sails whilst he sailed Finns competitively, and after that he set up in business to produce sails and hulls which dominated the Finn scene during most of the sixties and early seventies. |

|

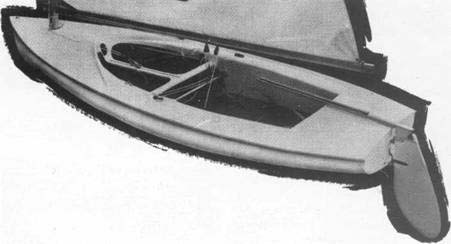

| The HVM Finn developed by Andre Nelis

|

|

| The Elvstrom GRP Finn |

|

A popular and successful hull in the late sixties was the American Newport hull. In 1969 the Newport was used to win the Gold Cup,

Europeans, North Americans and much more with sailors such as Jorg Bruder, Arne Akerson and Thomas Lundquist using these boats to good effect. |

|