1987

Great effort was going into the redrafting of the Rules for 1989 onwards. The IYRU Centreboard Boat Committee considered a draft in November and made many editorial proposals.

Actual rule changes were limited to alterations governing the introduction of advertising on boats, and minor definitions on sandwich construction (not allowed at that time) and on the definition of 'horizontal' for floorboards. |

1988

The new package of rales had been discussed for several years and was adopted by the IYRU.

1989

By 1989 the class had become very standardised. The best sailors were almost all using Vanguard boats built nearly ten years before, the Needlespar aluminium masts and the Dacron sails had hardly changed in a dozen years. This was starting to cause concern that the class would be seen as stagnant and would fail to achieve selection for the Olympic Games.

|

|

| Conducting a Lamboley swing test. |

|

Andrzej Ostrowski stepped down after seven years of steady leadership in the Technical Committee, culminating in the editing of a newly revised Rule Book. Richard Hart, an old Finn sailor, was asked to take over. The Technical Committee's brief was defined by Council "to make the Finn cheaper, easier to measure at championships, and suitable for a wider range of helmsman's weights".

|

1990

There was a marathon Technical Committee meeting at the Gold Cup in Thessaloniki, after which the IFA Council agreed and directed that the rules should be altered to encourage development of Fibre-reinforced plastic masts, with as few artificial constraints as possible. One comment was that "the new masts should not be a bad copy of the aluminium masts, which were themselves a bad copy of the old wooden masts."

This decision was enormously important. It demonstrated the change of attitude in the IFA Council to one which was more responsive to change in the class. For more than twenty five years it had been obvious that the mast should be as far forward as allowed in the boat, and there were always problems at measurement. As part of the 'mast' alterations, the Council agreed that the deck bearing position might be freed.

1991

The class mourned the death of Peter Mohilla, who as Chief Measurer had been a staunch guardian of the rales. He was replaced by another long time Finn sailor, Robert Laban, but during the following year Robert also died.

|

|

| Peter Mohilla conducting some experiments |

|

Rule changes made it easier to mould the stemband shape in plastic boats, and the class started to develop significant rule alterations to follow the 1992 Olympics.

A new Finn builder appeared: Pata from Hungary, who was associated with long-time Finn sailor Laszlo Zsindely.

1992

A rewritten sail measurement rale came into force, basically in accordance with the new IYRU Sail Measurement Instructions, but with one major difference: the half and three quarter height positions on the leech were to be measured from the Head Point, not by folding the leech. The difference allowed sails to be measured without folding and unfolding.

The class appointed Juri Saraskin as Chief Measurer.

1993

A number of major rule changes, the culmination of several years of discussion in the class, came into effect. Some changes simplified measurement and removed old problem areas: a requirement that the leading edge of the Centreplate be half round was deleted, some floorboard (inner bottom) rales were simplified, and the hulls were to be weighed without the mast, boom and rudder. Another series of changes facilitated the development of reinforced plastic masts. Minimum widths were specified for masts, but the fore and aft maximum dimensions were left large enough to accommodate older masts. Lead correctors were allowed up to 4 kilos, with a statement that the corrected minimum weight of 10 kilos would be reviewed after two years.

|

The mast hole position in the boat was freed. This simplified the new mast rule and enabled the rig to be moved. In the words of the official submission to the IYRU, henceforth "the boats would feel nicer in the waves".

New boats were starting to appear, such as the Devoti Finn (built in the UK and marketed from Italy) and the Lemieux Finn (built and marketed from Canada). Both boats were associated with leading Finn sailors. New plastic masts were used by several leading Finn sailors, coming second in the Finn Gold Cup and first in the Europeans. The new masts generally weighed about 7 or 8 kg, and the sailors complained bitterly about the big lead correctors to reach the 10 kg still required.

|

|

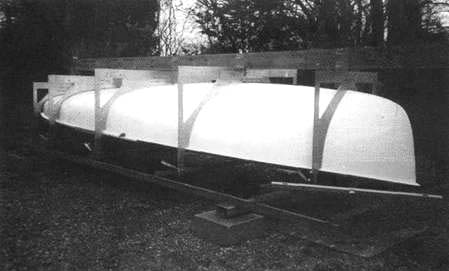

| Adequate buoyancy in the bow section is very important |

|

1994

For 1994, there were minor changes to the mast rule. Because the freeing of the mast position made the centreplate pin position less critical, the measurement of this position was simplified. At the Gold Cup, there were a considerable number of plastic masts, and a prototype sails made from unwoven (reinforced film) material. At the AGM, there was concern about the price of the new plastic masts.

1995

The minimum mast weight was reduced to 8 kilos. Plastic masts were becoming standard on the international circuit.

1996

At the Gold Cup, a 'ginger group' including several veterans (renamed masters) proposed a weight reduction for the hulls. By this time almost all boats built since 1980 were carrying between 5 and 10 kilos of lead correctors in the hull, and it was agreed that the hull weight should be reduced by 5 kilos. At the same time the Council instructed the Technical Committee to submit a rule change deleting the requirement for keel bands except forward of the centreplate slot.

There was considerable disquiet about the cost of some of the new plastic masts, in particular because they exploited the fore and aft tolerance to produce a partial wing section. The possibilities of building the masts over a standard mould (mandrel) and of tightening the fore and aft restrictions were discussed: the second was talked into oblivion at a long meeting of the full Council. In the end it was agreed that market forces would provide the only practicable control on the cost. There was also concern that new one piece sails might be introduced and would be excessively costly, so a rule was introduced requiring that the sails be made from panels of material not more than 1 metre wide.

|

The efforts of the class were concentrated upon selection for the 2000 Olympic Games.

1997

The rale changes discussed in 1996 came into effect. Keelbands were no longer required except forward of the centreplate slot, and the hull minimum weight was reduced by 5 kilos. At the same time the centreplate was required to conform to what had become standard: 8 mm anodised Aluminium. The minimum boom weight was increased by 0.5 kilo. A number of sails made from reinforced plastic film were in use at the Gold Cup. They went well, but did not outclass the latest Dacron sails.

|

|

| A purpose made jig to test hull shape against a set of certified templates |

|

1998

Since at the 2000 Olympics sailors could use their own boats, it was recognised that there would be increased pressure on the rules. For the first time, a rale appeared that there must be sheerguards! At the Gold Cup there were only about five woven sails in regular use. Many sails were made from reinforced plastic film, others from monofilm (without integral reinforcement). Prices and durability seemed to be satisfactory. There was concern that many masts and sails racing at intermediate level regattas had not been measured, and that these masts in particular were underweight.

1999

New rales required the measurement of masts and sails before they left the manufacturer. At the Gold Cup in January there were some sails made of ultra thin lightweight material, and the AGM instructed the Technical Committee to devise a rale to control the resulting expense.

Summary

The history of the Finn rules reflects the fascinating interplay between the Technical Committee (representing the International Finn Association and the majority of the anonymous Finn sailors) and keen competitors respectively builders, striving for higher performance. It is the story of a battle between

those, who wanted the Finn to remain a modern boat and those who were afraid that existing boats could be outmoded by new developments. It reflects a dramatic change between a document, meant to be a guide for the construction of the Finn Dinghy by home builders, to a sophisticated system of control of professional shipyards. It reflects the endeavour to find the proper pace of necessary changes over time, to go ahead with new ideas, without breaking the Finn Class apart. The problem was to allow the strongest and most ambitious to advance only at such a speed, that at least the majority of the ordinary sailors were able to keep pace. Up to the present time, the Finn Class has managed to stay on top of international dinghy development and to remain an Olympic Class for 50 years. Hopefully the Finn rales will continue to guide the Class in that manner far into the future.

|

|